[ad_1]

July 30th, 2024 by Chris Sotiro

Budd Lake, New Jersey’s largest natural freshwater body, was once an attractive vacation spot in North Jersey during the latter half of the 19th century for sunbathing, swimming, boating, and nearby attractions that have continued to today. Now, Budd Lake faces water quality impairments that threaten the recreation season and associated economic activities. Harmful algal blooms (HABs), caused by the overgrowth of cyanobacteria, have frequently shut down the lake for several weeks during peak summer months. Budd Lake is not just for boaters, anglers, and sportsmen; it serves a vital role in the watershed as the headwaters for the South Branch of the Raritan River, which supplies drinking water to over 1.8 million people living downstream. HABs degrade water quality to the point of toxicity, making this a matter of environmental concern and a public health dilemma. During severe bloom events, most water treatment facilities are not equipped to handle high levels of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in source water, putting otherwise healthy residents at risk of adverse health effects.

Harmful Algal Blooms

Human activities enable and exacerbate cyanobacteria growth when favorable environmental conditions are met, such as extreme heat and low flow rates. When nearby residents spray hazardous fertilizers on their lawns or when cars leak oil and grease while passing through US Route 46, those non-point source pollutants can be carried into the lake via stormwater runoff, acting as nutrients for cyanobacteria. Two main sources of nutrients are nitrogen and phosphorus, which can originate from residential, agricultural, or industrial sites, all of which can be found in proximity to Budd Lake. This problem is not confined to Budd Lake alone; major lakes throughout the state have fallen victim to HABs and restricted recreation to protect public health. Spruce Run Recreation Area in Hunterdon County – the third largest reservoir in the state—has already banned swimming for the rest of the summer after a HAB was detected in early July. Once a bloom forms, the affected water can harm humans and disrupt aquatic ecosystems.

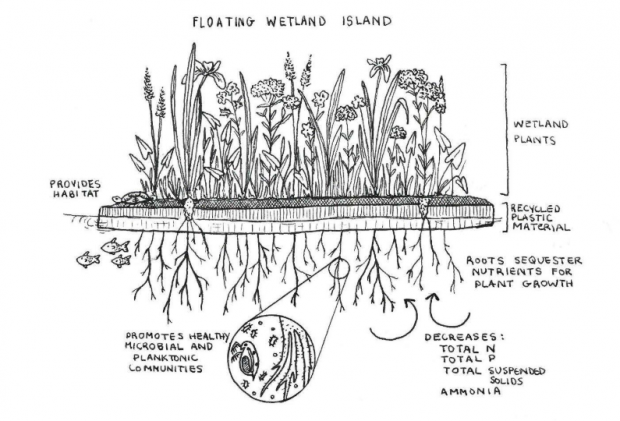

An example of a floating wetland island

Runoff from roadways and nearby neighborhoods is an issue that every municipality must grapple with. Existing gray infrastructure, such as traditional detention basins and pipes, are successful in redirecting stormwater, but fail to filter pollutants out of runoff or prevent contaminants from reaching nearby lakes and streams. While nonpoint source pollution is inevitable, whether or not those pollutants make it into water bodies is a question of effective stormwater planning. Green infrastructure is a low-cost, nature-based solution that sustainably improves water quality, absorbs greenhouse gas emissions, and provides new habitats for aquatic life. In the case of Budd Lake, floating wetlands are a form of green infrastructure that is being deployed to combat HABs by filtering nutrients from runoff that float at the water’s surface.

This illustration, sketched by Ivy Babson of Princeton Hydro, conveys the functionality of a floating wetland island.

Similar green infrastructure projects, such as rain gardens, porous pavement, and bioswales, can be retroactively installed on nearby properties to absorb stormwater and filter pollutants before they can discharge into Budd Lake. New Jersey Future’s Stormwater Retrofit Guide outlines best management practices for installing green infrastructure projects and methods to identify potential retrofit areas. This guide also showcases success stories of stormwater retrofit projects that have improved the health of watersheds throughout the State, such as those in Franklin and Lakewood Townships.

Stormwater basin retrofit in Franklin Township

Cleaning up Budd Lake will take years of collaborative, multi-agency effort. To combat HABs throughout the Garden State, $13.5 million in state and federal funding was made available for municipalities by Governor Murphy in 2019 for evaluation, treatment, prevention, and upgrades to sewer and stormwater systems. This funding, along with grant support from the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), allowed the Raritan Headwaters Association, Rutgers Cooperative Extension Water Resource Program, and Mount Olive Township to draft a watershed restoration and protection plan. This plan will improve Budd Lake’s water quality by incorporating green infrastructure at strategic sites around the lake to capture and filter large volumes of stormwater runoff.

As HABs have been occurring more frequently in recent years due to overdevelopment and steadily increasing annual precipitation rates, there is a growing need to curtail the use of environmentally harmful products while implementing nature-based solutions to mitigate the discharge of pollutants into major water bodies. New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the country, making it highly susceptible to pollution from stormwater runoff around residential, industrial, and commercial development. As of January 1, 2023, every municipality in the State must comply with new updates to the MS4 Tier A Permit, including the requirement to develop a long-term Watershed Improvement Plan, which must be finalized by the end of 2027. As municipalities draft this Plan in the coming years, it is crucial to explore opportunities to incorporate green infrastructure as a preventative measure that can capture, absorb, and filter runoff to prevent the growth of HABs at beloved community recreation sites and to safeguard water quality.

Tags: algal blooms, bacteria, clean water, cyanobacteria, green infrastructure, HABs, harmful algal blooms, health, local waterways, non-point source pollutants, outdoor recreation, pollutants, public health, Stormwater, stormwater runoff

[ad_2]

Source link