For more than seven decades, one New Jersey attorney stood quietly at the crossroads of law, power, and organized crime, representing some of the most feared and influential figures of the twentieth century while rarely seeking the spotlight himself. Now, at 93 years old, Chris Franzblau has finally pulled back the curtain on a career that placed him in the private rooms, whispered negotiations, and high-stakes legal battles that defined an era of American criminal history.

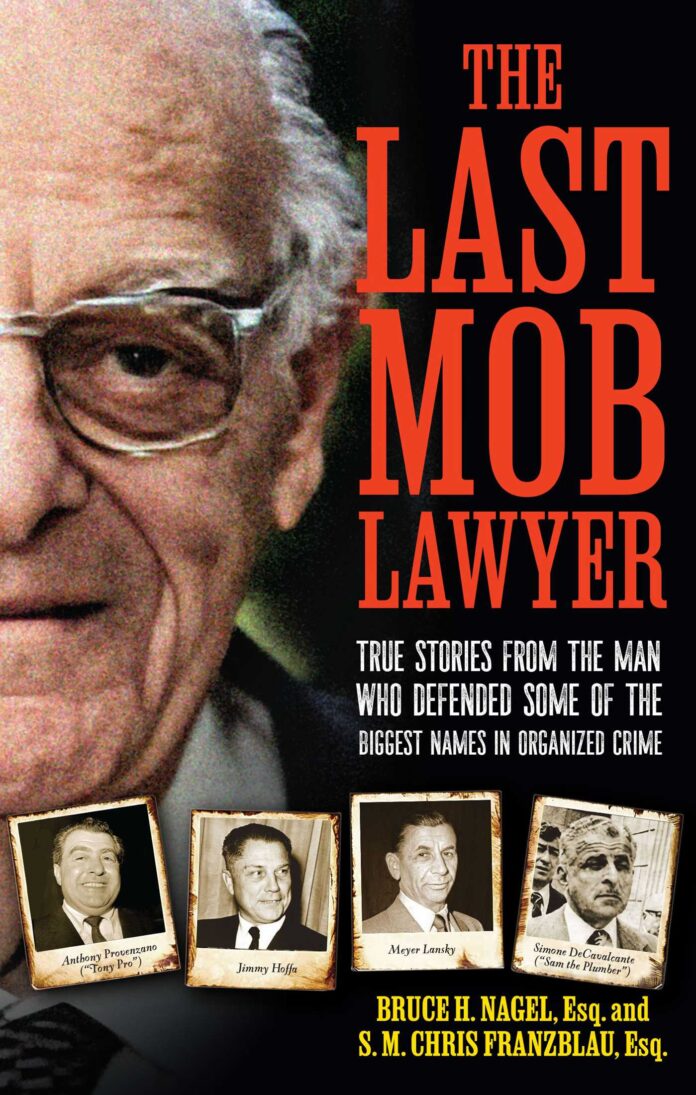

His newly released memoir, The Last Mob Lawyer: True Stories from the Man Who Defended Some of the Biggest Names in Organized Crime, offers a rare, firsthand account of what it meant to practice law in New Jersey when mob families, federal prosecutors, and labor unions collided daily in courtrooms, conference rooms, and back hallways across the state.

Franzblau was not merely a defense attorney who happened to represent controversial clients. He became, by reputation and by results, the lawyer trusted by some of the most powerful figures in organized crime to protect their freedom, their influence, and often their silence. In an industry built on loyalty, word-of-mouth, and absolute discretion, that trust became his defining professional currency.

His client list reads like a historical archive of American organized crime. He represented Genovese family boss Jerry Catena, Teamsters heavyweight Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano, and perhaps most famously, labor leader Jimmy Hoffa. Franzblau’s relationship with Hoffa extended far beyond courtroom appearances. In his book, he revisits one of the most enduring mysteries in American history: Hoffa’s disappearance.

According to Franzblau, a witness confided that Hoffa’s body was transported in a black Cadillac and buried at a construction site at the southern end of Broadway in Jersey City, near the Pulaski Skyway, during the 1970s. The alleged burial site, he explains, would place Hoffa beneath poured foundations that were later sealed and developed, creating a location entirely separate from the areas previously targeted by federal investigators and decades of high-profile searches. Franzblau does not frame the claim as speculation. He presents it as information delivered directly to him by someone he believed had personal knowledge of the event.

The memoir is not solely built around Hoffa’s disappearance. Instead, it unfolds as a sweeping chronicle of Franzblau’s seven-decade legal career in New Jersey, where he emerged as a central legal figure within the Genovese family’s operational orbit and a trusted advisor to senior leadership inside the Teamsters union during some of its most turbulent years.

What distinguishes Franzblau’s story from many organized crime memoirs is his professional origin. Before becoming one of the state’s most recognizable defense attorneys, he served as an Assistant United States Attorney. Earlier still, he worked as a Navy cryptographer and witnessed the Cuban Revolution firsthand, experiences that sharpened his understanding of secrecy, intelligence gathering, and the fragility of institutional power. That background, he argues, gave him a unique ability to anticipate prosecutorial strategies and navigate the psychological pressures that accompany federal investigations.

In the book, Franzblau also revisits one of the most controversial legal battles of his career: his efforts to prevent the extradition of Meyer Lansky. The case placed him directly against international authorities and forced him to confront the political complexities that surround high-profile criminal figures whose influence stretches across borders. Franzblau describes the case as a defining test of his legal instincts and his willingness to challenge government narratives when due process, in his view, was at risk.

The memoir further reaches into the cultural undercurrent of organized crime’s influence on American entertainment. Franzblau claims that organized crime intervention played a quiet but decisive role in rescuing the early careers of Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett, describing behind-the-scenes pressure and protection that allegedly shielded both artists at moments when industry gatekeepers were prepared to shut doors. Whether readers view these stories as revelations or provocations, they add an unexpected layer to the way power networks intersected with popular culture in mid-century America.

Another significant section of the book revisits Sam “The Plumber” DeCavalcante and the pivotal FBI wiretaps in 1965 that exposed the structure and hierarchy of New Jersey’s organized crime leadership. Franzblau offers personal insight into how those recordings reshaped the legal landscape for defense attorneys and permanently altered the balance between law enforcement and organized crime families operating in the region.

Throughout the memoir, Franzblau repeatedly returns to a central theme: the transformation of criminal defense law itself. He contrasts the slow, personal, reputation-based legal world of the 1950s and 1960s with today’s data-driven, media-saturated justice system. In his view, the profession he entered no longer exists in recognizable form. Attorneys once relied on trust built quietly over decades. Today, visibility and public narrative management often carry equal weight with courtroom skill.

The book spans approximately 208 pages, but its historical scope reaches far beyond its length. Franzblau reflects on how law enforcement tactics evolved, how informant culture reshaped organized crime structures, and how federal prosecution strategies became increasingly sophisticated as technology and surveillance expanded. For New Jersey readers, the memoir doubles as a detailed social history of the state’s legal and criminal institutions during the second half of the twentieth century.

Despite the notoriety surrounding many of his clients, Franzblau does not portray himself as a romantic figure in the criminal underworld. Instead, he frames his career as a study in legal boundaries, professional ethics, and the constant tension between defending constitutional rights and confronting the moral weight of the people who sought his representation. He writes candidly about moments when he questioned decisions, navigated personal risk, and wrestled with the emotional toll of representing clients who operated far outside society’s norms.

What makes Franzblau’s story especially compelling within New Jersey’s broader historical narrative is how deeply rooted his career was in the state’s courtrooms, neighborhoods, and political climate. The legal battles he describes unfolded in county courthouses, federal courtrooms, and union halls that remain active civic institutions today. His career offers a rare window into how organized crime once functioned openly enough to require a stable of elite legal specialists who knew both sides of the system intimately.

While Explore New Jersey most often highlights the state’s cultural, business, and community stories, the Franzblau memoir reminds readers that New Jersey’s identity has also been shaped by its complex legal and criminal history. That broader storytelling mission continues across the site, from investigative features to community reporting and even the statewide sports ecosystem covered through Explore New Jersey’s hockey coverage, where the same communities, neighborhoods, and families that appear in historical accounts continue to shape the modern fabric of the state.

For readers drawn to true crime, legal history, and the deeper mechanics of power behind public institutions, The Last Mob Lawyer offers a rare perspective that only one man could provide. Franzblau is not an outsider examining organized crime after the fact. He stood inside its legal machinery for more than 70 years, navigating conversations and conflicts that will never appear in official transcripts.

At an age when most careers are long concluded, Franzblau has chosen to document his experiences with remarkable directness. Whether readers are searching for new insight into Jimmy Hoffa’s fate, a clearer understanding of how New Jersey’s organized crime families operated, or a portrait of a legal profession that has largely disappeared, his memoir delivers a personal and often unsettling account of how justice, loyalty, and power intersected behind closed doors in the Garden State.

In telling his story now, Franzblau becomes exactly what the title suggests: the last living representative of a legal era shaped by whispered alliances, relentless federal scrutiny, and a criminal underworld that once operated in full view of New Jersey’s public life.