Prison gerrymandering is a practice that has long skewed political representation in the United States, inflating the voting power of rural districts while diminishing the voices of urban communities, particularly those of color. Despite common misconceptions, ending prison gerrymandering does not significantly affect federal funding formulas. Instead, it restores the core democratic principle of “one person, one vote,” ensuring that communities are represented fairly in the political process.

At its core, prison gerrymandering occurs when U.S. Census data counts incarcerated individuals in the location of their prison rather than their last known home address. Most incarcerated individuals cannot vote, yet their presence in prison districts artificially inflates the population count. This means that the residents of these districts have disproportionate voting influence compared to communities that lose representation when their residents are incarcerated elsewhere.

The consequences of this practice are profound and far-reaching. Distorted representation undermines the principle that each person’s vote should carry roughly equal weight. Urban areas, which supply the majority of the incarcerated population, often see their political influence diluted, while rural districts that host prisons gain additional power without corresponding voters. Communities of color are disproportionately impacted, as Black and Latino individuals are incarcerated at much higher rates. As a result, the very populations that most need advocacy and political attention find their voices minimized in legislative processes.

Moreover, prison gerrymandering can create skewed political incentives. Representatives in districts with large prison populations often focus their attention on the needs of the voting residents and prison employees rather than advocating for policies that could benefit incarcerated people. Critics have argued that this imbalance even encourages the construction of more prisons in rural areas to maintain or expand political clout.

A common misconception is that ending prison gerrymandering would harm federal funding for these districts. While census data informs the allocation of federal dollars, the redistricting data used to draw legislative boundaries does not directly determine funding formulas. Ending this practice primarily corrects representation rather than redistributing federal money, debunking a longstanding argument against reform.

New Jersey has taken decisive action to address this issue. In 2018, the state passed legislation mandating that incarcerated individuals be counted at their last known residential address for the purposes of state legislative redistricting. This law ensures that urban communities receive fair representation and that rural districts are not artificially empowered by the presence of prison populations. The New Jersey Department of Corrections collects and provides de-identified residential data to the Secretary of State to implement this process accurately.

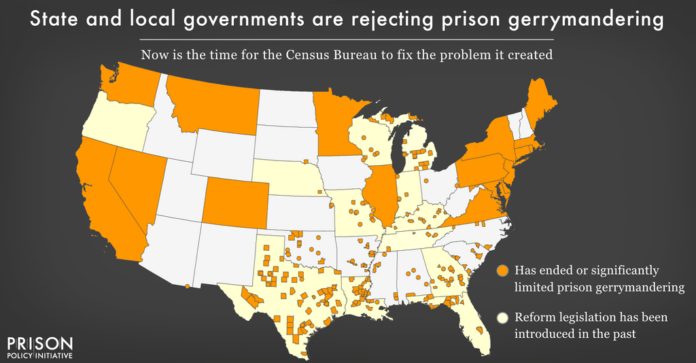

The legal foundation for these reforms is solid. The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld similar measures, such as Maryland’s law requiring prisoners to be counted at their home addresses, setting a precedent that enables other states to pursue fair redistricting initiatives. To date, at least 13 states have implemented policies to end prison gerrymandering, signaling a growing recognition of its undemocratic effects and the need to uphold electoral equity.

Correcting prison gerrymandering is more than a technical adjustment—it is a matter of justice, equity, and democracy. By counting incarcerated individuals in their home communities, states ensure that residents have an accurate voice in the political process, especially those who have been historically marginalized. New Jersey’s example demonstrates that legislative action can realign political power to better reflect the true population, enhance accountability, and restore fairness to a fundamental aspect of governance.

For more insights on criminal justice reform and related advocacy efforts, visit Sustainable Action Now’s Private Prisons page to learn how policy changes are reshaping the landscape of incarceration and representation in the U.S.

Prison gerrymandering may seem like a technical issue, but its implications for democracy are profound. Ending it ensures that communities of color, urban residents, and families affected by incarceration are fairly represented, and that the integrity of elections reflects the principles upon which the nation was founded. New Jersey’s legislative reform stands as a model for other states seeking to correct this inequity and uphold the democratic rights of all citizens.