On February 8, 2026, the Super Bowl stage finally reflected the sound, language, and cultural influence that have dominated global music for more than a decade. At Super Bowl LX inside Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, California, Bad Bunny delivered a landmark halftime performance that rewrote the playbook for what the NFL’s most-watched entertainment moment can look and sound like. The Puerto Rican superstar became the first solo Latin artist to headline the Super Bowl halftime show, and he did it almost entirely in Spanish—without compromise, without translation, and without diluting the identity that built his career.

For millions watching across the United States, including fans throughout New Jersey who have long embraced Latin pop and reggaetón as part of the state’s cultural fabric, the moment felt less like a breakthrough and more like a long-overdue recognition. From Newark to Paterson to Union City, Bad Bunny’s music has already been woven into everyday life, nightlife, and local radio rotations for years. Sunday night simply brought that reality to the center of the sports world.

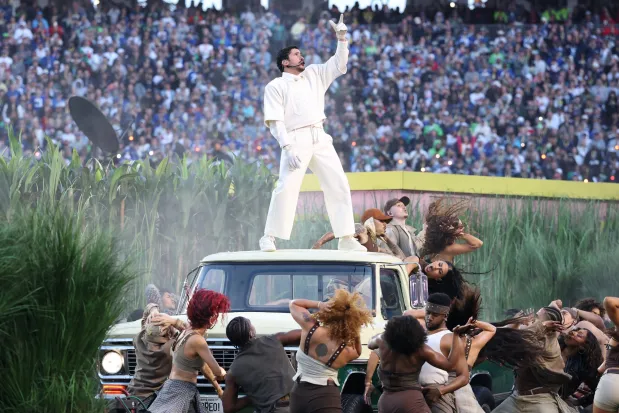

The 13-minute performance unfolded as a carefully staged tribute to Puerto Rico, blending contemporary pop spectacle with unmistakable cultural symbolism. Instead of opening with pyrotechnics and spectacle alone, the show introduced a visual narrative built around familiar island imagery—sugar cane fields stretching across the stage, domino tables set with animated players, and a piragua cart serving shaved ice at the edge of the performance space. The design choices were deliberate and unmistakable, transforming the NFL’s biggest platform into a living, moving neighborhood scene that echoed street life and community traditions.

Bad Bunny’s story-driven Super Bowl halftime show redefined what the biggest stage in sports can mean—and honestly, what I think was overlooked is how family-driven the messaging in that production was, which I found genuinely entertaining.

Full disclosure: I had never heard a note of his music before last night. I get it. It’s good—it’s alive, it’s likable—and it would probably resonate even more if I remembered any Spanish. But what truly stood out to me was the emphasis on family within the Latino community. The kids, the adults dancing with the kids, the cake being cut, and the family gatherings from scene to scene were what stayed with me. That’s what I took away from the performance, which is a complete irony considering what some people were opposed to about him performing in the first place.

What also made Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime performance resonate far beyond its chart-topping soundtrack was not just who was on the stage, or even how historic the moment itself was. It was the way the entire production unfolded like a living narrative. This was not a static concert dropped into the middle of a football broadcast. It was a carefully built, scene-by-scene story that moved with purpose, emotion, and cultural intention, creating one of the most immersive halftime shows the NFL has ever presented.

From the opening visual, it was clear that the performance was designed to communicate something larger than a setlist. The staging felt closer to a short film or theatrical production than a traditional pop spectacle. Each segment transitioned into the next with visual continuity, as if the audience was being guided through a neighborhood, a memory, and a shared cultural experience rather than simply watching an artist perform hit songs on a massive platform.

That storytelling approach is what separated this show from the long history of halftime productions that rely heavily on overwhelming scale, extreme lighting effects, and rapid-fire medleys designed primarily to dazzle. Bad Bunny’s performance did not abandon spectacle, but it placed narrative at the center. The environment itself became a character. The audience moved from scene to scene through symbolic representations of everyday Puerto Rican life, community gathering spaces, and cultural traditions that are rarely given this kind of international spotlight during a global sporting event. Actually, I took it as that this is a typical slice of life omn a Sunday in Los Angeles or in any place where Latinos are populated in America.

The production design told its own story before a single lyric was sung. Sugarcane fields, domino tables filled with animated players, and the presence of a piragua cart were not decorative details—they were deliberate cultural signposts. For viewers who recognize those images instantly, the message was personal and unmistakable. For those encountering them for the first time, the show became an invitation to understand a culture that exists well beyond stereotypes and surface-level references.

They also took a page from the old Survivor TV show finales, when Jeff Probst would walk with the urn through the actual forest and then emerge into the CBS studio “jungle” with the audience and contestants. That’s how this production began, which threw me for a second. Then it moved into the stadium sets built as sugarcane fields.

Also—does Puerto Rico actually have a lot of sugarcane? I once visited a plantation in Hawaii a long time ago. I had no clue it was part of the industry in PR.

Anyway, what made the experience especially powerful was how naturally the transitions unfolded. Instead of abrupt lighting changes and sudden camera cuts, the performance flowed with cinematic pacing. Each visual shift mirrored the emotional arc of the music itself. High-energy sequences gave way to reflective moments, then returned to celebration without breaking the narrative thread. It felt like watching a story evolve rather than simply watching a performance change tempo.

This approach elevated the music in a way that pure production scale never could. Songs were not isolated moments. They were chapters. The choreography, camera movement, and staging worked together to support a broader emotional rhythm. The result was a halftime show that demanded attention not only for its sound, but for its meaning.

For many viewers across New Jersey, where Latin music and Caribbean culture are deeply woven into daily life, the show landed with particular resonance. In communities throughout the state, Spanish-language music has long dominated playlists, local festivals, nightclubs, and community events. Seeing that sound and identity presented without compromise on the world’s largest sports stage was both validating and overdue.

The performance quietly but decisively reinforced a cultural shift that has already been underway for years. Spanish-language music is no longer positioned as a crossover experiment or a secondary market. It is global pop culture. The halftime show did not attempt to translate that reality for mainstream audiences. Instead, it trusted viewers to meet the music where it already exists.

That confidence extended to the language itself. The overwhelming majority of the performance remained in Spanish, and it never treated that fact as a barrier to accessibility. The production assumed that rhythm, visual storytelling, and emotional connection would carry the moment forward. And they did.

The presence of high-profile guest performers and celebrity cameos added energy and visibility, but they never overtook the central narrative. Each appearance felt integrated into the story rather than inserted for social media impact. The set’s central “La Casita” concept created a shared space where artists, actors, and performers existed within the same cultural environment instead of orbiting around the star of the show.

That sense of community is what gave the production its emotional depth. It did not frame success as an individual achievement. It framed it as collective identity reaching a global platform together.

The creative direction also reflected a larger evolution in how halftime shows are being conceptualized. In recent years, the NFL has increasingly leaned into performances that acknowledge cultural history and musical legacy. This show went even further by placing lived cultural experience at the center of its creative vision. It did not rely on nostalgia. It relied on representation.

For Explore New Jersey readers who closely follow how sports, culture, and entertainment intersect, the performance felt especially aligned with how local fandom continues to evolve. New Jersey’s sports culture has become inseparable from the music, fashion, and global influences that shape younger generations of fans. That same cultural crossover continues to influence how football is consumed and celebrated across the state, a connection regularly explored in Explore New Jersey’s football coverage, where the relationship between community identity and professional sports is becoming increasingly visible.

Beyond its artistic success, the halftime show also carried a subtle but powerful industry message. It demonstrated that an artist can lead the world’s most visible entertainment platform without reshaping their sound to fit traditional expectations of what mass-market American pop is supposed to look like. The production trusted authenticity as its commercial engine.

That trust was rewarded with overwhelming audience engagement, immediate online conversation, and a cultural moment that extended well beyond the confines of the broadcast itself. Clips of the performance circulated instantly across social platforms, not because of pyrotechnics or shock value, but because of how clearly the story came through on screen.

The closing visual, paired with the message that “The only thing more powerful than hate is love,” did not feel like an obligatory sign-off. It felt like the final line of a carefully written script. After a performance centered on community, heritage, and shared identity, the message landed with emotional clarity rather than generic optimism.

What ultimately made Bad Bunny’s halftime show exceptional was not its scale, its celebrity presence, or even its historical significance as a milestone for Latin artists. It was the creative choice to treat the stage as a narrative platform. It showed that halftime entertainment can be cinematic, culturally specific, and emotionally grounded without sacrificing energy or mass appeal.

This performance will be remembered not simply as a breakthrough moment for Spanish-language music, but as a blueprint for how the NFL and its entertainment partners can rethink what storytelling looks like at the intersection of sports and culture. It confirmed that authenticity does not limit reach. It expands it.

Bad Bunny opened the show with Tití Me Preguntó, instantly igniting the crowd and setting a playful, high-energy tone. The track’s opening beats reverberated through the stadium as dancers flooded the field, dressed in bright, street-inspired outfits that mirrored the everyday fashion and movement of Puerto Rican youth culture. From there, the performance flowed seamlessly into Yo Perreo Sola, leaning into the artist’s long-standing commitment to gender expression, autonomy, and social visibility through his music and visual presentation.

As the show built momentum, Bad Bunny transitioned into a tightly choreographed medley that included Safaera, Party, and Voy a Llevarte a PR, each segment layered with shifting lighting effects and moving stage platforms that recreated neighborhood blocks and open-air party spaces. Rather than isolating individual hits, the medley format highlighted how his catalog functions as a cultural ecosystem—one sound feeding into another, one era blending into the next.

Midway through the set, the atmosphere shifted with EoO, offering a moment of rhythmic reset before the first surprise guest took the stage. Lady Gaga emerged for a salsa-inspired reinterpretation of Die With a Smile, marking one of the most unexpected and stylistically ambitious collaborations ever attempted during a halftime show. I would also say to them, “Get a room, please,” because I think she really wants him—and if she is married, I’m sorry to the husband. But, instead of leaning into pop spectacle, the arrangement introduced live percussion, brass flourishes, and a distinctly Caribbean rhythmic backbone, creating a bilingual performance that honored both artists’ musical identities while allowing the Latin arrangement to take the lead.

The collaboration was followed by Baile Inolvidable, one of the emotional anchors of the set, before Bad Bunny pivoted to Nuevayol, delivering a subtle nod to the long-standing connection between Puerto Rico and New York—a cultural bridge that remains deeply relevant to New Jersey communities shaped by both migration and music. The moment resonated strongly for viewers across the region, where Latin heritage and East Coast identity continue to intersect in everyday life, from local clubs to college campuses and professional sports venues.

The second guest appearance further solidified the show’s cultural weight. Ricky Martin joined Bad Bunny on stage for Lo Que Le Pasó a Hawaii, creating a generational crossover that symbolized the evolution of Latin pop from its late-1990s mainstream breakthrough to its current era of global dominance. The pairing connected two artists who represent different chapters of the same cultural ascent, standing together on the sport’s most visible platform.

Beyond the music, the performance was packed with recognizable faces woven directly into the set. The show’s centerpiece, a stylized neighborhood home known as La Casita, became a focal point for celebrity cameos that included Pedro Pascal, Jessica Alba, Cardi B, and Karol G. Rather than serving as detached celebrity cutaways, the appearances were integrated into the scene itself, reinforcing the concept of community gathering and shared cultural space.

The final stretch of the performance returned to Bad Bunny’s socially conscious catalog. El Apagón brought its familiar political and infrastructural undertones into the halftime spotlight, reminding viewers that his music frequently doubles as cultural commentary. Café Con Ron followed, restoring celebratory energy while maintaining the performance’s distinctly Latin sonic palette.

The finale, DtMF, closed the show on an emotional high, bringing dancers, musicians, and guest performers together across the field in a unified visual tableau. As the last notes faded, a massive screen rose above the stage, delivering a clear and deliberate message to the global audience: “The only thing more powerful than hate is love.”

In a year when social division continues to dominate headlines, the message carried added weight—particularly within a performance that centered Spanish-language music, immigrant identity, and Caribbean heritage without framing them as novelty or exception.

From a broader cultural and industry standpoint, the halftime show represented a significant shift for the NFL and its entertainment partners. For decades, Latin artists have appeared as collaborators, guest performers, or crossover novelties. This performance placed a Spanish-speaking global superstar at the center of the production, on his own terms, supported by his own catalog, his own imagery, and his own narrative.

For New Jersey audiences—especially those who closely follow how music, sports, and culture intersect across the state’s diverse communities—the moment also reflected how Latin influence has already become a foundational part of mainstream American entertainment. That same cultural crossover can be seen throughout the region’s professional sports scene and fan communities, a connection regularly explored in Explore New Jersey’s football coverage, where local passion and global influence increasingly share the same stage.

While the halftime performance dominated conversation across social media and broadcast recaps, the game itself delivered a decisive outcome. The Seattle Seahawks defeated the New England Patriots 29–13, closing Super Bowl LX with a clear statement on the field. Yet by the time the final whistle sounded, the night had already secured its place in history for reasons that extended well beyond the scoreboard.

Bad Bunny’s halftime show will be remembered not simply as a musical milestone, but as a cultural realignment. It proved that Spanish-language music no longer needs translation to command the world’s largest stages. It showed that authenticity, when presented without dilution, can resonate across borders, demographics, and fan bases. And for millions of viewers—including those watching from New Jersey’s living rooms, sports bars, and community spaces—the performance offered a powerful reminder that the future of American pop culture is not defined by one language, one genre, or one background, but by the diversity that has already reshaped it.

For viewers watching from New Jersey living rooms, packed sports bars, and community spaces throughout the state, the show offered more than a halftime distraction. It offered representation, creative ambition, and a powerful reminder that the future of American pop culture is not defined by one sound, one language, or one identity. It is being shaped, scene by scene, by the diversity that has already transformed the country’s cultural landscape.