[ad_1]

July 30th, 2024 by Tim Evans

The rising costs of housing in New Jersey are affecting everyone, especially individuals and households at the lower end of the income spectrum. New Jersey’s unique Mount Laurel doctrine is meant to address the need for housing for lower-income households, but it also indirectly has a major effect on the supply of market-rate multi-family units in the process. The process by which towns satisfy their affordable housing obligations does not guarantee a full range of housing options for a full range of household types and incomes. The Mount Laurel requirements ought to serve as a prompt for towns to think holistically about their housing supply in general—how much and what types of housing will they need to accommodate the needs of future residents?

Panelists in the session “Knowing the Numbers: Housing Allocation, Patterns of Development and the Future of Housing” at the 2024 Planning and Redevelopment Conference discussed the current state of affairs in housing in New Jersey, for affordable housing and beyond. Moderator Creigh Rahenkamp, Principal of CRA, LLC, and Tim Evans, Research Director at New Jersey Future, gave background about the housing supply in general, and Katherine Payne, Director of Land Use, Fair Share Housing Center; Graham Petto, Principal, Topology; and David Kinsey, Partner, Kinsey & Hand talked about what to expect from the latest changes to the state’s system of incentivizing affordable housing. Panelists all agreed that the Mount Laurel system is necessary but not sufficient to provide the full range of housing options that New Jersey’s future population will need.

“Mount Laurel” and Affordable Housing

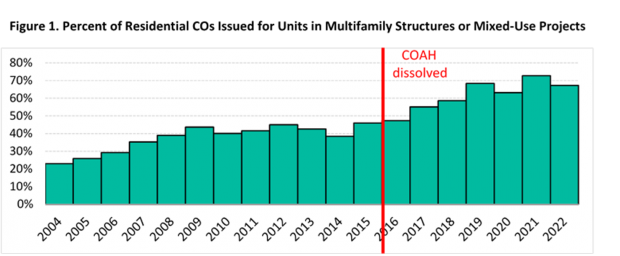

The Mount Laurel doctrine refers to a series of New Jersey Supreme Court decisions that direct municipalities to provide their “fair share” of the regional need for low- and moderate-income housing. For many years, enforcement of the requirements was the responsibility of the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), but the Council was effectively dissolved in 2015 when the Court deemed it ineffective and handed enforcement authority back to the judicial system. Payne cited her organization’s 2023 report Dismantling Exclusionary Zoning: New Jersey’s Blueprint for Overcoming Segregation to point out that the annual production of affordable units increased substantially after 2015 under the subsequent more rigorous court oversight. (She pointed out that the vast majority of affordable housing is produced in the form of multifamily housing.) The report also found that most of the overall growth in multifamily housing (primarily apartments) over the same time period has been achieved in inclusionary Mount Laurel projects, projects that contain both income-restricted and market-rate units, to the extent that 81% of all multifamily units built since 2015 were built in connection with the Mount Laurel process. Reinforcing this relationship, Evans cited data showing certificates of occupancy (COs) for multifamily housing rising in the post-COAH era (see Figure 1 ) to the point where multifamily units now account for more than half of all housing production. “This shift in permitting activity is being driven by Mount Laurel-associated re-zonings,” Payne said.

Production of multifamily housing has increased steadily in the post-COAH era. More than 4 out of 5 multifamily units built since 2015 are associated with Mount Laurel projects, either as affordable units or as market-rate units that are part of mixed-income projects.

Administration of the Mount Laurel process has recently undergone another significant change with the passage of new legislation, in the form of Assembly Bill 4/Senate Bill 50 this year. Among other things, the legislation sets up an oversight mechanism within the executive branch and directs the Department of Community Affairs to implement a methodology for determining municipal affordable housing obligations, based on three factors—income capacity, non-residential property valuation, and developable land. While the rules will take time to create, Petto said municipalities can and should get started now in preparing plans for compliance, including thinking about where in town the Mount Laurel units will be located and how to earn extra credit for certain types and locations. Kinsey mentioned that the legislation allows for bonus credits for such features as proximity to public transportation, special-needs or supportive housing, and redevelopment of a retail, office, or commercial site.

Redevelopment as the New Paradigm

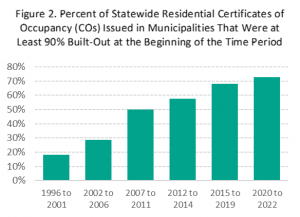

Many new Mount Laurel units will be constructed in redevelopment areas, if the overall pattern of population growth in recent years is any indication. Evans showed that most of the state’s housing growth over the last decade and a half has been happening in already-built-out areas (see Figure 2 ).

Redevelopment is the new normal: An increasing share of New Jersey’s housing growth has been happening in already-built places.

It is clear that “built-out” does not necessarily mean “full,” and that redevelopment areas offer plenty of opportunities for municipalities to create more housing, both for Mount Laurel and market-rate. As such, the new legislation requires municipalities to develop plans for “conversion or redevelopment of unused or underutilized property, including existing structures if necessary, to assure the achievement of the municipality’s fair share” of affordable housing.

The “Missing Middle” Is Still Missing

Payne reminded listeners that the Mount Laurel doctrine originally arose when the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that municipalities cannot practice “exclusionary zoning,” by which they effectively exclude lower-income households by writing their zoning codes to allow nothing but single-family detached homes, which are less affordable to households of modest means. Such zoning is still very common: “About 75% of land in major US cities is zoned exclusively for single-family housing, which has implications for access to opportunity,” Payne said.

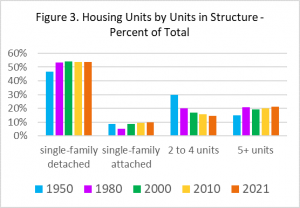

While the Mount Laurel process was set up to ensure the provision of housing for lower-income households, it does not address other types of housing that are left out by exclusionary zoning and are thus in short supply. The wide array of housing options between single-family detached units on one end of the scale and large apartment buildings on the other are often called the “missing middle,” because many places simply don’t plan for them. This includes options like duplexes, triplexes, small apartment buildings, apartments above stores, and accessory dwelling units (ADUs), a category that itself includes small, separate units that are attached to or on the same property as a larger unit, like above-garage apartments or “in-law suites.” Evans illustrated how housing units in 2-, 3-, and 4-unit buildings have declined as a share of total housing units, from 30% of all units in 1950 to half that share as of 2021 (see Figure 3 ). Kinsey further noted that the number of units in structures with 2 to 4 units has actually decreased in absolute terms, dropping from about 514,000 in 1970 to about 490,000 in 2020.

“Missing middle” housing options in buildings with 2 to 4 units have declined dramatically since 1950 as a share of total housing units.

Another conference session, “We’re Missing Middle Housing in New Jersey: How to Fix It,” was devoted entirely to these missing options and strategies to bring them back. One of the speakers in that session, Karla Georges of the national American Planning Association, identified states where “missing middle” housing bills have passed, including Washington, Colorado (HB1316 and HB1175, and Arizona. Kinsey mentioned one modest New Jersey effort, bill S2347 currently being considered by the legislature, that would authorize ADUs statewide. Meanwhile, some New Jersey municipalities have legalized ADUs on their own, without waiting for statewide legislation.

In any event, while New Jersey is ahead of most of the rest of the country in having the Mount Laurel doctrine and its supporting legislation, this is insufficient as a mechanism for ensuring the production of a full range of housing types, without which people will continue to migrate out of New Jersey in search of cheaper options. As New Urbanist pioneer Peter Calthorpe has observed at the national level, “We cannot build this country on subsidized housing. We’re never going to get the end result. We have to create the context, the policies, and the zoning that make middle housing viable and located in the right locations.” New Jersey now needs to follow the lead of other states in exploring strategies to break the stranglehold of single-family zoning, so that households of all incomes can afford to call New Jersey home.

Tags: 2024 NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference, Affordable housing, Housing, housing and equity, missing middle, Redevelopment

[ad_2]

Source link